Welcome to Part 2 of my Cheat Sheet for Stats series, sure to make you the life of the party! In case you missed it, Part 1 covered measures of center and spread. In Part 2 we’ll dive into measures of position and location within a dataset – specifically how to calculate, apply, and interpret them.

Measures of Position

Comparing month to month sales volume or current housing prices within your neighborhood are easy to make without involving additional calculations. However, sometimes metrics aren’t exactly comparable in absolute terms. For example, sales volume from 1989 versus 2015. Or current housing prices in Atlanta versus San Francisco. So we typically “normalize” these metrics by adjusting for inflation or cost of living so we can compare relative values.

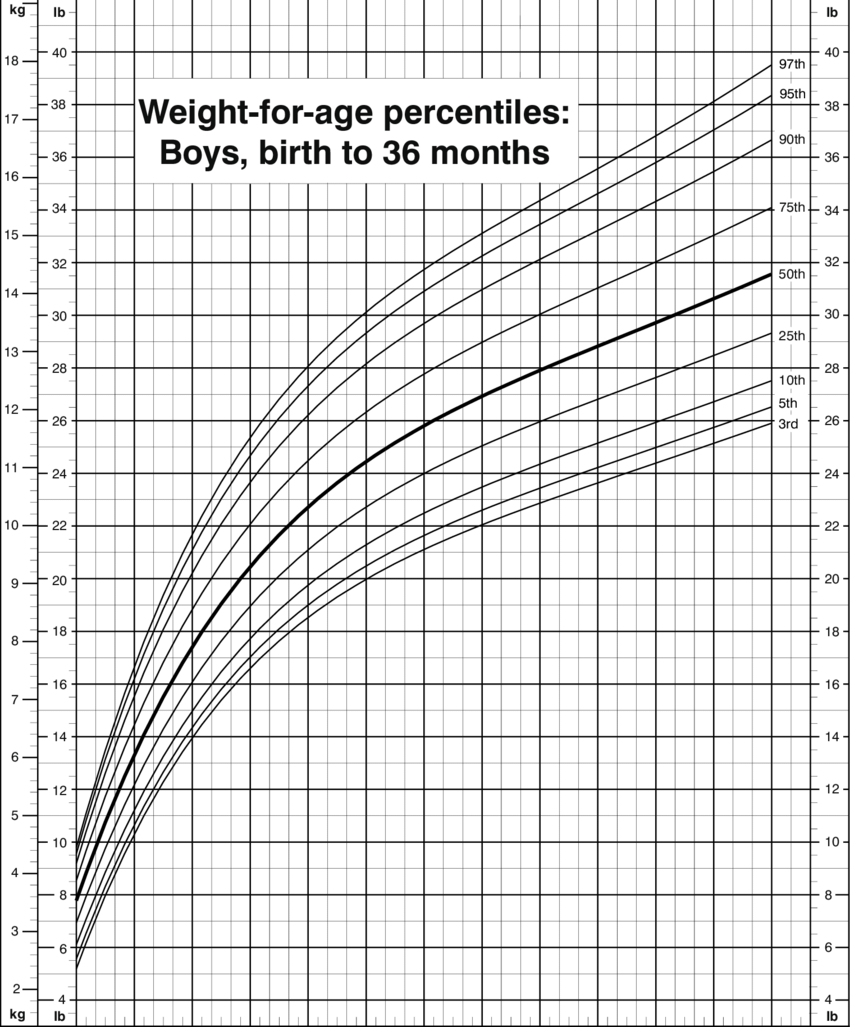

Another way of comparing considers relative position. Percentiles, quantiles, and z-scores measure the location of a value in relation to other values in a dataset. Once you know the price of a house in Atlanta relative to the rest of the Atlanta housing market, and the price of a house in San Francisco relative to the rest of the San Francisco housing market, you can see how those two housing prices compare to each other.

Percentiles

Percentiles describe the position of a data point relative to the rest of the dataset using a percent. That’s the percent of the rest of the dataset that falls below the particular data point.

Finding an Unknown Percentile

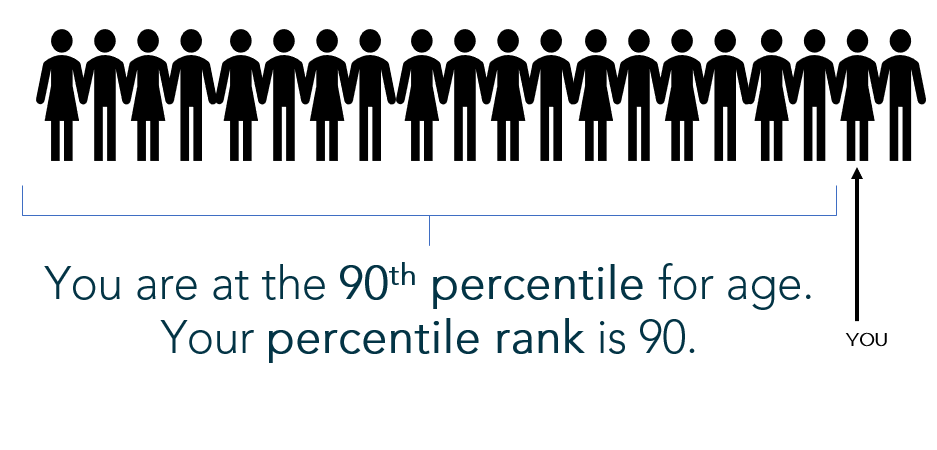

Example: Pretend you’re the 2nd oldest out of a group of 20 people. To find your percentile, count the number of people YOUNGER than you (18) and divide by the total number of people:

18/20 = 0.9, or the 90th percentile

(Note: By calculating percentile using the “percent less than” formula above, the computation disallows a 100th percentile (which is not a valid percentile); however, it forces the lowest value to the 0 percentile (which is also invalid). Another popular variation on this calculation computes the percent less than AND equal to: There are 19 people at your age or younger, so 19/20 is 95th percentile. This version of the calculation fixes the “0 percentile” problem but allows the possibility for an invalid 100th percentile. Both versions of the percentile calculation are acceptable and there is no universally “correct” computation.)

Finding a Given Percentile

Example: You want to determine what height marks the 58th percentile of the 20 people. You’ll multiply the 20 people by 58%, or 20*(0.58) = 11.6. This number is called the index. Round to the nearest whole number 12 – therefore, the 12th height in your group of 20 people roughly falls at the 58th percentile.

Quantiles

Quantiles break the dataset up into an equal number of n pieces. They signal reference points (or positions) in the dataset to which individual data points can be compared. Specific examples of quantiles are deciles (slicing the data into 10 equal pieces), terciles (3 equal pieces), and quartiles (4 equal pieces). I’ll elaborate using quartiles, but all quantiles follow the same logic:

Quartiles

Quartiles break the dataset up into 4 equal pieces so data points can be compared within the dataset relative to the four quarters of data.

I love watching football, which is broken up into four quarters. If I turn the TV on and the game has already started, I know how far the game has progressed in time relative to the quarter displayed on the screen.

For data:

- Lower Quartile (Q1) – Roughly the 25th percentile. 25% of the data falls below this point and 75% lies above.

- Median (Q2) – Roughly the 50th percentile, marks the position of the middle value where half fall above and half fall below this point

- Upper Quartile (Q3) – Roughly the 75th percentile. 75% of the data falls below this point and 25% lies above.

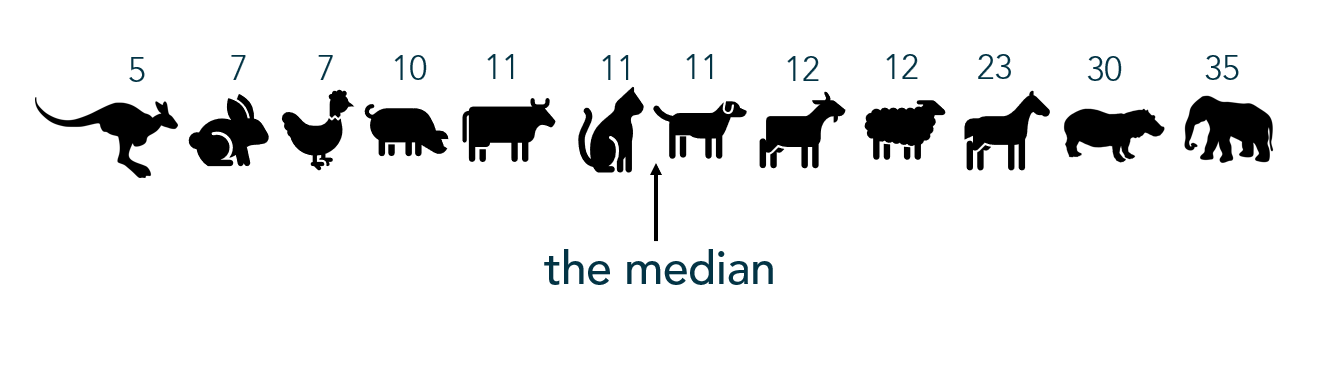

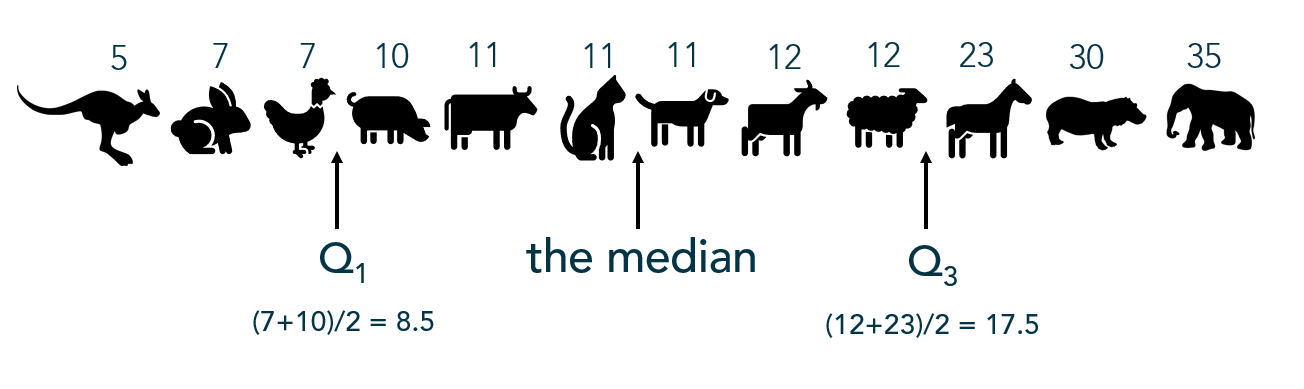

Quartiles are found using these steps:

- Arrange the data from least to greatest.

- Find the median, the middle number. (If there are two numbers in the middle, find the average of the two.)

- Using the median as the midpoint, the data is now split in half. Now find the middle value in the bottom half of values (this is Q1).

- Lastly, find the middle number of the top half of values (this is Q3).

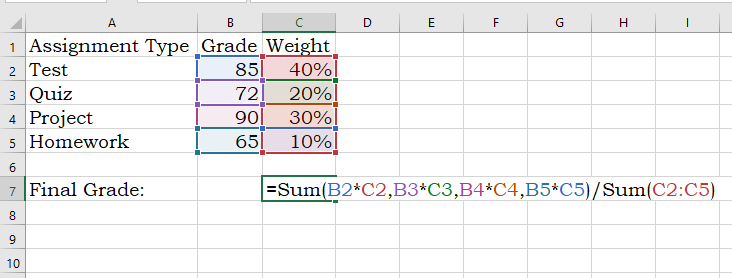

Example: The following values represent the lifespan of a sample of animals. What values break these lifespans into quartiles?

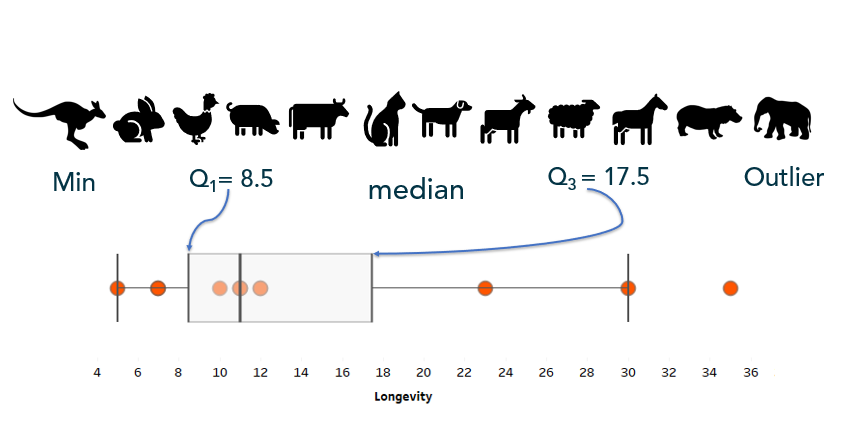

Often quartiles are displayed visually with a box-and-whisker plot:

Z-Scores

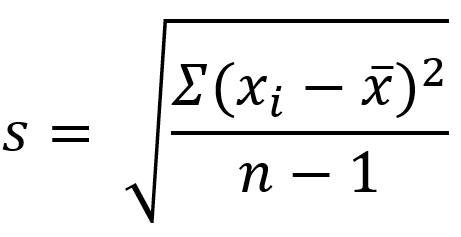

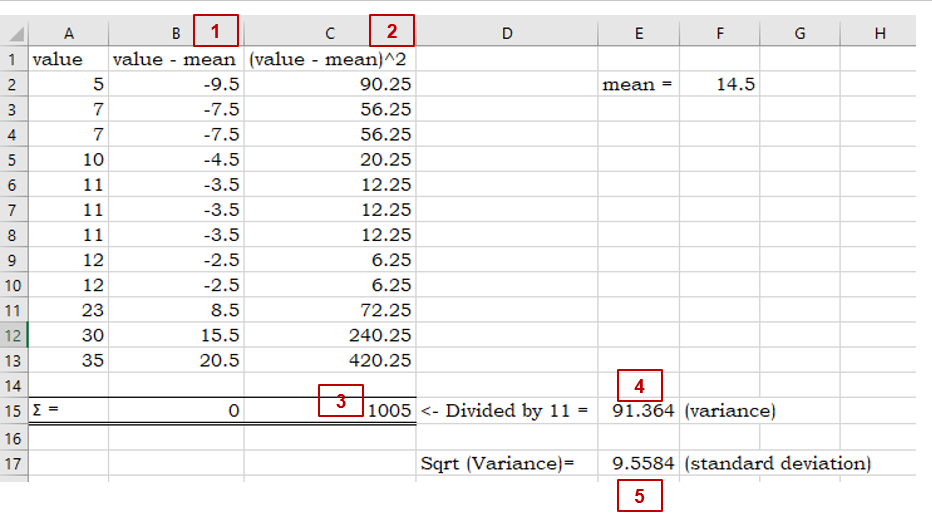

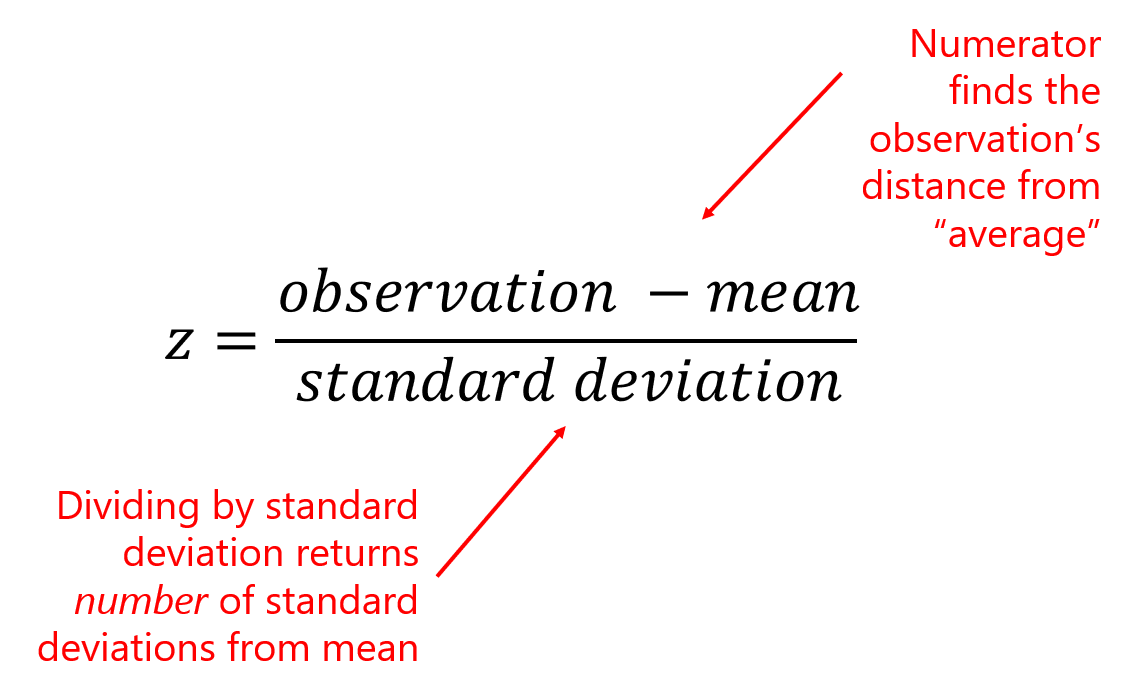

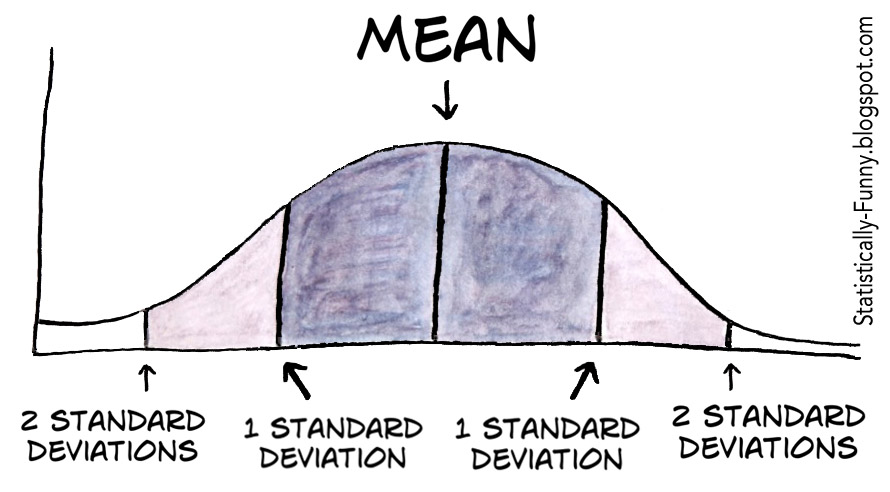

A z-score indicates how many standard deviations a value falls above or below the mean (average). A value with a positive z-score lies above the mean while a value with a negative z-score falls below the mean. Z-scores are a way of standardizing values in order to compare them using relative position.

To calculate a z-score, subtract the average of the population/dataset (mean) from the data point (observation), then divide by the standard deviation of the population/dataset:

Example:

In 1927, Babe Ruth made history hitting 60 home runs in one Major League Baseball season. Only four people have been able to break Ruth’s record (though Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa have broken that record 2 and 3 times, respectively). In 2001, Barry Bonds set the most recent record, hitting 73 home runs in a single season.

But just how does Barry’s home run performance compare to Babe’s? Many outside factors such as bat quality and pitcher performance could impact the number of homeruns hit by a MLB player. So how did these athletes compare to their peers of the time?

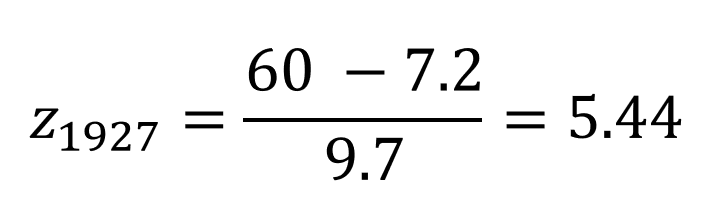

The 1927 league home run average was 7.2 home runs with a standard deviation of 9.7 home runs. While the 2001 league average was an astounding 21.4 home runs, with a standard deviation of 13.2 home runs.

To properly compare these heavy hitters, we need to determine how they preformed relative to the peers of their era by standardizing their absolute HR numbers into z-scores:

While both athletes displayed phenomenal performances, Babe Ruth could still argue his status of home run champion when comparing in relative terms.

If you automatically think of a bell-shaped, normal curve when you hear “z-score”, you’re not alone. That’s a common connection because of the way we initially introduce z-scores in stats courses:

But z-scores can apply to ANY distribution because they are a way to compare data values using relative position. That is, z-scores “standardize” the data values from absolute to relative metrics.

The Altman Z-score

The Altman z-score is used to predict the liklihood a company will go bankrupt. The Altman z-score applies a weighted calculation based on specific predictors of bankruptcy. This article gives an excellent overview for those interested in calculating and interpreting Altman z-scores.

Next up in Part 3: Counting principles, including permutations and combinations. Because the combination for your combination lock is actually a permutation.